Uterine bleeding in the Emergency department

/Tired of reading? Prefer to absorb your MedEd through your wonderful powers of hearing? Check out our podcast by clicking HERE

Uterine bleeding is a common presentation to the Emergency Department and rarely these patients are SICK. When they come in sick, its not the time to be googling the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologist (ACOG) recs on managing uterine bleeding. Here we review the proper management of the pregnant, post-partum, and non-pregnant patient with uterine bleeding.

NON-PREGNANT PATIENT

Think Critically

This post will focus on the things we can do in the department both medically and procedurally to stabilize patients with acute abnormal uterine bleeding. However, we must always think about why a patient is experiencing abnormal bleeding. In the case of acute severe uterine bleeding unrelated to pregnancy, there are three specific etiologies to consider[1]:

COAGULOPATHY

Consider the possibility of undiagnosed coagulopathy (most commonly this is Von Willebrand’s disease)

Significant bleeding in the younger woman could be the first presentation

ANTICOAGULATION

The indications for anticoagulation continues to expand and the adult woman with uterine bleeding should be asked about anticoagulant use.

FIBROIDS

These can cause bleeding on their own. They can bleed spontaneously or when they outgrow their blood supply.

After stabilization of the unstable patient, the OBGYN national society (ACOG) recommends assessing for the cause of bleeding with the PALM–COEIN system.[2]

https://www.researchgate.net/figure/FIGO-classification-of-causes-of-AUB-PALM-COEIN_fig1_284797278

Hemodynamically Unstable

In the hemodynamically unstable patient, the initial focus is on stabilization. Establish two large bore IVs, perform an airway assessment, intubate as needed, and transfuse blood and blood products. While the data on massive transfusion protocols have all been born out of the trauma literature, a 1:1:1 transfusion of RBCs, FFP, and platelets seems to be the most appropriate approach in the hemorrhagic shock patient (PROPPR trial).

1. SOURCE CONTROL

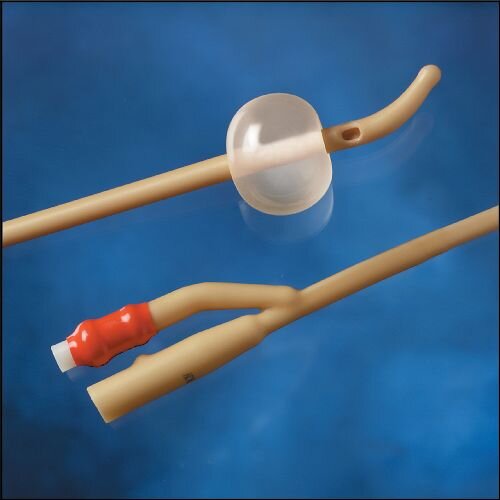

In the case of brisk uterine bleeding, uterine tamponade may help to prevent further losses while the above replacement occurs. This can be accomplished in the following steps:

Speculum pelvic exam

Sterilize/clean the cervix with iodine applicators

Grab and stabilize the cervix with a single toothed forceps

Advance a 30 cc foley through the cervix and inflate to light resistance

2. ESTROGEN

Estrogen promotes the growth of the endometrium over denudated tissue. It stabilizes lysosomal membranes and promotes ground substance formation.

High dose estrogen is considered one of the first line medical treatments (besides blood products). The most commonly cited literature showing efficacy was a small study in 1982 where 34 women were randomly assigned to either placebo or Premarin (the US brand name for estrogen - 25 mg in 5 ml saline over 2 minutes). In this study, there was no difference in bleeding cessation rates between the two groups at the three hour mark, but at 5 hours significantly more (72%) women in the estrogen group had bleeding cessation than the placebo group (38%).[2,3]

Interestingly, this is the only drug approved by the FDA for acute uterine bleeding.

***It is important to note that premarin carries a risk of thrombosis. The contraindications to infusion include breast cancer, active or past venous thrombosis or arterial thromboembolic disease, and liver dysfunction/disease. It should be used with caution in patients with cardiovascular or thromboembolic risk factors.***

3. TRANEXAMIC ACID [TXA]

This fibrin stabilizing agent has been proven in the literature to save lives in the post-partum period (see below) as well as patients with chronic abnormal uterine bleeding. In cases of significant blood loss leading to hemodynamic instability and the need for blood products, TXA may help stabilize thrombus and decrease/prevent further losses. It is well studied in post-partum bleeding, but there is less robust evidence in the non-pregnant patient. There is a cochrane review on the topic showing low-moderate quality evidence showing TXA improved heavy menstrual bleeding.[4]

Hemodynamically Stable

In less severe bleeding states, combined oral contraceptive pills (OCP) or progesterone based formulations (for example medroxyprogesterone acetate) are an option. These cases are often amenable to the patient scheduling with their OB/GYN and finding the OCP or other hormone therapy that is ideal for them, their schedule, and their lifestyle.

PREGNANT/POST-PARTUM PATIENT

Postpartum hemorrhage is the most common cause of peripartum maternal death. The potential for significant blood loss is heightened in late pregnancy as the uterine artery blood flow is approximately 500-700 mL/min![5] Hemorrhage is usually prevented by two things - contraction of the myometrium and release of local hemostatic factors. In the vast majority of cases, a lack of or insufficient myometrial contraction plays a role, as uterine atony is by far the most frequent cause of post-partum hemorrhage (PPH).

Other possible causes include retained placental fragments, placenta accreta, and uterine injury/laceration (with its own risk factors of induced labor and instrument delivery).

The definition of primary PPH is blood loss >500 mL after vaginal delivery and >1000 mL after C-section in the first 24 hours. Secondary PPH occurs after the first 24 hours and is less commonly encountered in the Emergency Department.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Image source: https://caehealthcare.com/blog/saving-lives-with-simulation-training-in-qbl-and-pph-recognition/

1. The Basics - The first step to treating PPH is uterine massage, increasing myometrial contraction. After this, there are further escalating approaches to decreasing hemorrhage, as described below:

2. Medications:

Oxytocin: This is often given routinely after delivery of the placenta to help decrease the potential for hemorrhage and has been shown to reduce the risk of progression to PPH.[5] Dosing starts at 10-40 U infused via a crystalloid solution. 10 U intramuscularly is another approach. Higher doses are sometimes used (ie 80 U in 500 cc NS).

Carboprost: A prostaglandin analog, carboprost increases muscle tone of the smooth muscle-based myometrium. It is used at a 250 mcg dose IM which can be repeated to a total of 2 mg. As a smooth muscle contracting agent, contraindications to its use include severe asthma.

Methylergonovine: An ergot derivative, which also increases the tone of uterine contraction. Dosing is 0.2 mg, also given IM. Slightly different contraindications exist here, which are more cardiovascular given the ergot family of medication. The contraindications include significant hypertension, coronary artery or other arterial occlusive disease processes (CVA, Raynauds).

Tranexamic acid: As noted above, TXA has been proven safe and efficacious in trauma patients. Recently, studies have shown similar safety and efficacy in postpartum obstetric patients. In particular, the WOMAN trial was published in Lancet in 2017. In this international randomized trial across 21 countries, women with PPH were given either saline or 1 g of TXA IV as an infusion. The data showed a statistically significant decrease in mortality, especially if given within the first 3 hours of hemorrhage (1.2% in TXA group vs 1.7%, RR 0.69).[7]

Other Agents: Misoprostol is a uterotonic drug similar to carboprost (prostaglandin) that can be administered orally, vaginally or rectally. It can be given in cases where there are contraindications to the IV or IM drugs noted above. It is more commonly used in the prevention of PPH. Dinoprostone is a similar agent that can be given rectally or vaginally. In general, knowing the two or three most commonly and readily available agents for use is most important. The use of these alternatives should be discussed with our OBGYN colleagues.

3. Procedures - As with any patient experiencing hemorrhage from an identifiable source, direct source control is always desirable. There are several situations in which direct intervention is needed:

Laceration repair: Lacerations to the cervix and perineal region occur not infrequently. Suturing and repair of these lacerations (via re-approximation or hemostatic sutures like the figure of 8) can decrease bleeding.

Uterine tamponade: Given that uterine atony is the primary cause of PPH and the potential blood volume the atonic uterus can contain, tamponade is unlikely. This intervention may not prevent significant losses or hemodynamic decompensation. It could, however, be done in patients with active or expected continued bleeding as it has the potential to limit losses.

Retained products: When there is a clinical concern for incomplete removal of the placenta (evaluation of the placenta shows missing elements, difficult or overly forceful delivery of the placenta, etc), there may be a need for removal of the products of conception. Roughly 10% of PPH is from this etiology.[7] While not a routine procedure of the EM physician, a manual extraction with a sterile glove to scrap away the retained placenta may be necessary.

Tired of reading? Prefer to absorb your MedEd through your wonderful powers of hearing? Listen to the associated podcast below:

Peer Reviewed by Becca Bloch, MD and Jeffrey A. Holmes, MD

References:

Ely JW1, Kennedy CM, Clark EC, Bowdler NC. Abnormal uterine bleeding: a management algorithm. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006 Nov-Dec;19(6):590-602.[Pubmed]

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 557: Management of acute abnormal uterine bleeding in nonpregnant reproductive-aged women. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Apr;121(4):891-6. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000428646.67925.9a.[Pubmed]

DeVore GR, Owens O, Kase N. Use of intravenous Premarin in the treatment of dysfunctional uterine bleeding--a double-blind randomized control study. Obstet Gynecol. 1982 Mar;59(3):285-91.[Pubmed]

Bryant-Smith AC, Lethaby A, Farquhar C, Hickey M. Antifibrinolytics for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2018, Issue 4. Art. No.: CD000249. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000249.pub2 [Pdf]

Belfort MA. Overview of Post Partum Hemorrhage. UpToDate. Accessed 3/15/2020.

Begley CM, Gyte GM, Devane D, McGuire W, Weeks A. Active versus expectant management for women in the third stage of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Mar 2;(3):CD007412. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007412.pub4.[Full Text]

WOMAN Trial Collaborators. Effect of early tranexamic acid administration on mortality, hysterectomy, and other morbidities in women with post-partum haemorrhage (WOMAN): an international, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017 May 27;389(10084):2105-2116. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30638-4. Epub 2017 Apr 26.[Pdf]

Wall, Ron, Robert Hockberger, Marianne Gausche-Hill. Labor and Delivery and Their Complications. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. 9th edition. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders, 2017.